- Home

- ::

- Why You Shouldn't Touch a Chemotherapy Patient: Myths and Safety Tips

Why You Shouldn't Touch a Chemotherapy Patient: Myths and Safety Tips

Chemotherapy Infection Risk Calculator

Patient Safety Assessment

Estimate infection risk based on neutrophil count and current symptoms

When you hear the phrase “don’t touch a chemo patient,” it can feel harsh or confusing. The truth is, it’s not about being rude - it’s about protecting someone whose immune system is seriously weakened by treatment. Below we’ll break down why touching can be risky, bust common myths, and give you clear steps to stay safe while still showing love.

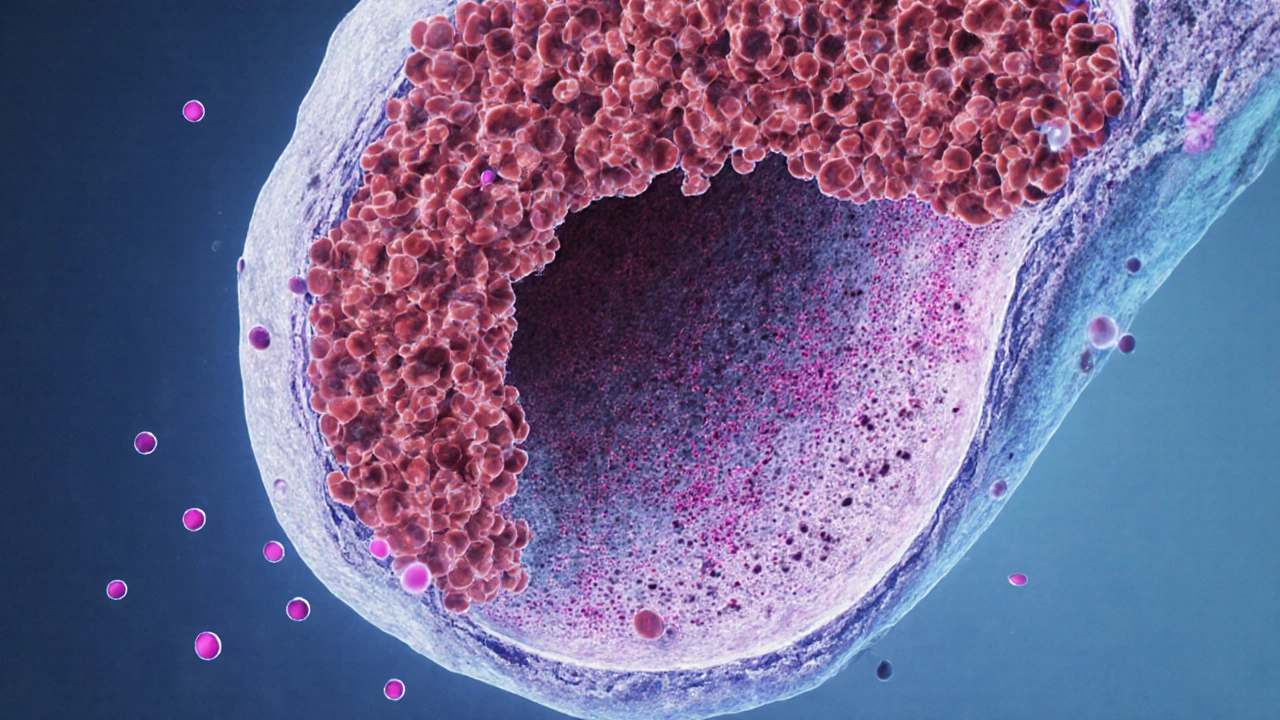

How chemotherapy changes the body’s defenses

During cancer treatment, doctors often use drugs that target fast‑growing cells. While they aim at tumor cells, they also hit healthy bone‑marrow cells that produce white blood cells. The result is Neutropenia, a condition where the neutrophil count drops below 1,500 cells per microliter. Neutrophils are the foot soldiers that fight bacterial infections, so a low count leaves the patient vulnerable.

In addition to neutropenia, chemotherapy can cause Immunosuppression by reducing lymphocytes and impairing the skin’s barrier function. These changes mean that everyday germs - even the ones you can’t see - become a serious threat.

Why touching a chemo patient can be dangerous

Most people think “a little touch won’t hurt.” But consider these facts:

- Skin flora transfer: Our hands carry bacteria like Staphylococcus aureus. A simple handshake can move millions of organisms onto a patient’s skin.

- Respiratory droplets: Talking, coughing, or even breathing releases tiny droplets that settle on surfaces and wounds.

- Compromised skin: Chemotherapy often causes dry, cracked skin or mouth sores, providing entry points for microbes.

When a chemo patient with neutropenia encounters these germs, their body may not mount a quick response, leading to fevers, sepsis, or treatment delays.

Myth vs. Fact: Common misconceptions about touching

| Myth | Fact |

|---|---|

| “A quick hug won’t spread infection.” | Physical contact can transfer skin flora and respiratory droplets, especially if hands aren’t clean. |

| “Only hospital staff need to worry about germs.” | Family, friends, and caregivers are equally likely to be vectors because they visit often. |

| “If the patient feels fine, they’re not at risk.” | Infections can develop silently; a fever may appear days after exposure. |

| “Wearing gloves is optional.” | Gloves, combined with proper hand hygiene, drastically cut bacterial transfer. |

Practical steps to protect a chemotherapy patient

- Wash hands thoroughly: Use soap and water for at least 20 seconds. If water isn’t available, a hand sanitizer with at least 60% alcohol works.

- Wear disposable gloves: When touching any part of the patient’s skin, use clean gloves and discard them after use.

- Limit crowd exposure: Keep visitors to a minimum and avoid bringing the patient to public places during low‑blood‑count periods.

- Disinfect surfaces: Wipe down bedside tables, phones, and remote controls with an EPA‑approved disinfectant.

- Stay home if sick: Even a mild cold can become dangerous for someone with a compromised immune system.

- Ask the care team: Follow specific hospital protocols; some centers provide a “no‑touch” consent form outlining safe practices.

When it’s okay to touch - with precautions

Physical comfort is still important. The key is to make contact safe:

- Use a clean, soft cloth to gently pat a shoulder after washing your hands.

- Offer emotional support verbally or through video calls if the patient’s blood counts are critically low.

- If the care team approves, wear a mask and gloves while assisting with feeding or personal care.

Always ask the patient or nurse for the latest neutrophil count; if it’s below 500, extra caution is needed.

Caring for a chemo patient at home

Home care brings extra responsibilities. Here’s a quick checklist to keep the environment safe:

- Room cleanliness: Change bedding weekly, vacuum with a HEPA filter, and keep the room well‑ventilated.

- Food safety: Prepare meals that are cooked thoroughly; avoid raw eggs, unpasteurized dairy, and undercooked meat.

- Pet hygiene: Keep pets clean, limit them from sleeping on the patient’s pillow, and wash hands after handling animals.

- Medication management: Store antibiotics and anti‑nausea pills out of reach of children and pets.

Regularly review the patient’s blood‑test results with the oncology team. If neutropenia persists, doctors may prescribe prophylactic antibiotics or growth‑factor injections (e.g., filgrastim) to boost white‑blood‑cell production.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can I hug a chemo patient if I wash my hands first?

Hand washing reduces risk, but a hug still transfers skin flora and respiratory droplets. If hugging is essential, wear a clean glove and a mask, and keep the contact brief.

Do all chemo patients need the same level of protection?

Protection level varies with the patient’s neutrophil count and type of regimen. Those on high‑dose alkylating agents often have deeper neutropenia and need stricter measures.

Is it safe to hold a chemo patient’s hand during a conversation?

Only if both parties have clean hands and wear gloves. Otherwise, keep a small distance and use verbal reassurance.

Should I wear a mask when visiting a chemo patient?

Yes, especially if you have a cold or if the patient’s count is below 1,000. A surgical mask blocks most respiratory droplets.

What should I do if I accidentally touch a chemo patient without cleaning my hands?

Immediately wash your hands with soap and water, inform the patient’s nurse, and monitor the patient for any signs of fever or infection over the next 48‑72 hours.

By understanding the science behind chemotherapy‑induced immunosuppression and following simple hygiene habits, you can keep your loved one safe while still providing the emotional support they need. Remember: it’s not the touch you avoid, but the germs you keep at bay.

Health and Wellness

Health and Wellness

Write a comment